Lesson Overview

The student should develop knowledge of the elements related to a Go-Around/Rejected Landing. The student will understand the importance of a prompt decision and have the ability to quickly and safely configure the airplane and adjust its attitude to accomplish a go-around. The student will perform the maneuver to the standards prescribed in the ACS/PTS.

References : Airplane Flying Handbook (FAA-H-8083-3C, page(s) 8-12), POH/AFM

| Key Elements |

|

| Elements |

|

| Schedule |

|

| Equipment |

|

| IP Actions |

|

| SP Actions |

|

| Completion Standards |

The student shows the ability to recognize when a go-around is needed and promptly configures the airplane and adjusts its attitude to safely execute the rejected landing. |

Instructor Notes

| Attention |

There will be times when we have to discontinue a landing and set up for another one. This may be a result of a dangerous situation or may just be necessary to re-establish an approach. Either way, we definitely want to know what we’re doing as we’re getting closer and closer to the ground. |

| Overview |

Review Objectives and Elements/Key ideas |

| What |

A go-around is the discontinuance of a landing approach in order to make another attempt to land under more favorable conditions (it is an alternative to any approach or landing). The go-around is a normal maneuver that may at times be used in an emergency situation. It is warranted whenever landing conditions are not satisfactory and the landing should be abandoned or re-setup. |

| Why |

The need to discontinue a landing may arise at any point in the landing process and the ability to safely discontinue the landing is essential, especially due to the close proximity of the ground. |

Lesson Details

Not every approach to landing will be perfect, and various circumstances can cause the need for a go-around. Reasons to go around are, in fact, numerous. A list of possible reasons are :

-

Unstable/poor approach

-

ATC request due to traffic management needs

-

Obstruction (deer, coyote, pickup truck, broken plane, etc.) on the runway

-

Overtaking another plane

-

Wind shear

-

Wake turbulence

-

Whenever safety dictates a go-around

These reasons (and more) are all examples of reasons to execute a go-around. It is almost never a bad decision to go around and set up the approach again, and is often the hallmark of superior airmanship.

Promptly Deciding to Discontinue a Landing

The go-around maneuver is not inherently dangerous. It only becomes dangerous when delayed or poorly executed. Delaying the decision generally stems from two source, the first being landing expectancy and the other being pride. Landing expectancy is the anticipatory belief that conditions are not as bad as they look, and that the approach can be terminated successfully. Pride comes in when it is believed that performing a go-around is an admission of failure. In fact, it is more the case that it is an expression of superior airmanship.

The earlier problems are recognized, and acted upon (by executing a go-around) the safer the go-around/rejected landing operation can be. It is, therefore, important to make a prompt decision, and then to act in a positive, not tentative, manner. So once you make the decision to go around, commit to it and don’t change the decision and try to land. Once a go-around is initiated, complete it.

Cardinal Principles of the Procedure

The improper execution of the go-around procedure stems from a lack of familiarity with the three cardinal principles of the procedure.

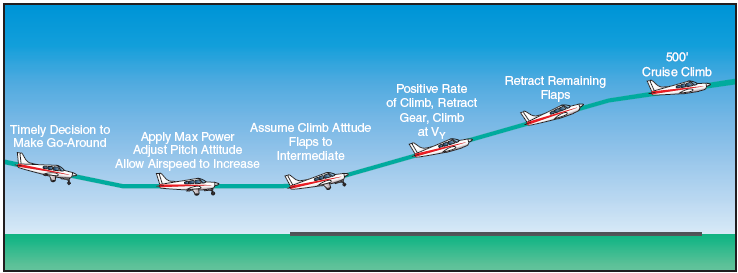

Power is the pilot’s FIRST concern. The instant the pilot decides to go-around full or maximum takeoff power should be applied. It should be applied smoothly and without hesitation. Full power must be maintained until flying speed and controllability are restored. Applying partial power is never appropriate.

Recognize that with full power torque effect and turning tendencies will require right rudder inputs. Anticipate this need and bring the rudder pressure in promptly.

It is also important to recognize that a go-around is battling inertia. The aircraft had been on a descending path, and the downward inertia must be slowed, stopped, and then reversed. This takes time, which is another reason to initiate a go-around as early as possible.

The attitude of the aircraft is always critical when near the ground. Two much nose up or nose down can create problems. When adding power it is very important to avoid letting the nose rise prematurely. An attitude must be maintained that will allow the aircraft build speed before any effort is made to gain altitude. The pitch attitude must slow/stop the descent, and airspeed must be build up to well beyond the stall speed.

If the nose is raised too early (a natural tendency) the aircraft may not climb at all until it has reached a safe airspeed. Instead the pilot should pitch for Vy (or Vx if circumstances warrant), and when time permits re-trim the airplane for the climb out. The trim is useful because the transition from low power descent to high power climb can result in fairly high stick forces. Quickly reliving those pressures will ease the go-around workload.

Along with the above concerns, the aircraft needs to be reconfigured for the climb. The first concern are the flaps and then the gear (if retractable). The flaps must be removed in a controlled manner, and not taken out completely all at once. Going directly to a cruise setting will result in an immediate loss of lift and risks the aircraft settling to the ground. Therefore remove flaps in a controlled manner as detailed in the POH/AFM.

After a positive rate of climb has been established (and not before) the landing gear should be retracted. Only retract the gear after the initial/rough trim has been established and when it is certain that the aircraft will remain airborne. Do not retract the gear in a descent. A good rule of thumb is to retract the flaps when the aircraft has reached Vy and when the aircraft is at a safe altitude

The flaps are raised before the gear for two reasons. The first is that the flaps produce more drag than the gear, so removing that drag first gives the most immediate benefit. Finally, in the event that the go-around is botched and the aircraft does touchdown, having the gear out will mitigate damage.

Control Pressures

When takeoff power is applied the airplane’s nose will rise suddenly. It will be necessary to hold forward pressure to maintain straight and level flight and to reach a safe climb attitude. It should be remembered that the aircraft has been trimmed for the approach, which is a low power/low airspeed condition and is quite different from the trim needed for a full power climb.

Additionally, the nose will veer to the left. This is due to P-Factor and Torque Effect which will required right rudder to compensate. Trim should be used to relieve adverse control pressures and to assist in maintaining the proper attitude. Achieving an initial rough, imperfect, trim will serve as a good first approximation of the needed trim. Fine tuning the trim can wait.

During the Climb Out

As the airplane climbs the pilot should maintain a ground track parallel to the extended centerline that allows the pilot to see the runway. Maneuver to the side of the landing/runway area to clear the area and avoid obstructions. This is particularly true in the case where the go-around was initiated due to another (potentially departing) aircraft on the runway. Maintaining visual contact with the obstruction (particularly if it is traffic) is important. Wind correction may be needed, and if necessary climb at Vx instead of Vy to avoid obstructions.

Communication

Controlling the aircraft is job #1, but once that is achieved the next priority is to communicate intentions. Let the tower or CTAF know that you are "Going Around". Remember the rule ….. Aviate, Navigate, then Communicate. Fly first, then deal with the radios.

Common Errors:

-

Failure to recognize a situation where a go-around/rejected landing is necessary

-

Hazards of delaying a decision to perform a go-around/rejected landing

-

Improper power application

-

Failure to control pitch attitude

-

Failure to compensate for torque effect

-

Improper trim procedure

-

Failure to maintain recommended airspeeds

-

Improper wing flaps or landing gear retraction procedure

-

Failure to maintain proper track during climb-out

-

Failure to remain well clear of obstructions and other traffic

Conclusion

The go-around is a very important maneuver that is essential in an emergency situation. The pilot’s first concern is power, followed by the establishing the correct attitude, and configuration.

ACS Requirements

To determine that the applicant:

-

Exhibits instructional knowledge of the elements of a go-around/rejected landing by describing:

-

Situations where a go-around is necessary.

-

Importance of making a prompt decision.

-

Importance of applying takeoff power immediately after the go-around decision is made.

-

Importance of establishing proper pitch attitude.

-

Wing flaps retraction.

-

Use of trim.

-

Landing gear retraction.

-

Proper climb speed.

-

Proper track and obstruction clearance.

-

Use of checklist.

-

-

Exhibits instructional knowledge of common errors related to a go-around/rejected landing by describing:

-

Failure to recognize a situation where a go-around/rejected landing is necessary.

-

Hazards of delaying a decision to go-around/rejected landing.

-

Improper power application.

-

Failure to control pitch attitude.

-

Failure to compensate for torque effect.

-

Improper trim technique.

-

Failure to maintain recommended airspeeds.

-

Improper wing flaps or landing gear retraction procedure.

-

Failure to maintain proper track during climb-out.

-

Failure to remain well clear of obstructions and other traffic.

-

-

Demonstrates and simultaneously explains a go-around/rejected landing from an instructional standpoint.

-

Analyzes and corrects simulated common errors related to a go-around/rejected landing.

-

Complete the appropriate checklist.

-

Make radio calls as appropriate.

-

Make a timely decision to discontinue the approach to landing.

-

Apply takeoff power immediately and transition to climb pitch attitude for VX or VY as appropriate +10/-5 knots.

-

Retract the flaps, as appropriate.

-

Retract the landing gear after establishing a positive rate of climb.

-

Maneuver to the side of the runway/landing area when necessary to clear and avoid conflicting traffic.

-

Maintain VY +10/-5 knots to a safe maneuvering altitude.

-

Maintain directional control and proper wind-drift correction throughout the climb.

Same as the Private Pilot, except:

-

Configure the airplane after a positive rate of climb has been verified or in accordance with airplane manufacturer’s instructions. (Replaces steps 5 & 6)

-

Maintain Vy +/-5 knots to a safe maneuvering altitude.